Page Content

ATHABASCA ARCHIVES

ATHABASCA ARCHIVES

Photo of Toles School near Amber Valley, Alberta, circa 1940s

Black teachers have contributed significantly to educating young Albertans, becoming role models and inspiration for students, being active in ATA locals and setting up community organizations.

WE TEND TO THINK OF BLACK TEACHERS AS NONEXISTENT in early 20th century Alberta, but there were actually a number of Black teachers from that era. Many taught initially in schools and communities established by Black pioneers and later in all-white or mixed school settings. Those who began teaching during the early 1900s lay a path for others who arrived in the 1960s as professionals to fill a shortage primarily in northern communities and more recently from a variety of Black Francophone and Anglophone countries.

Early years

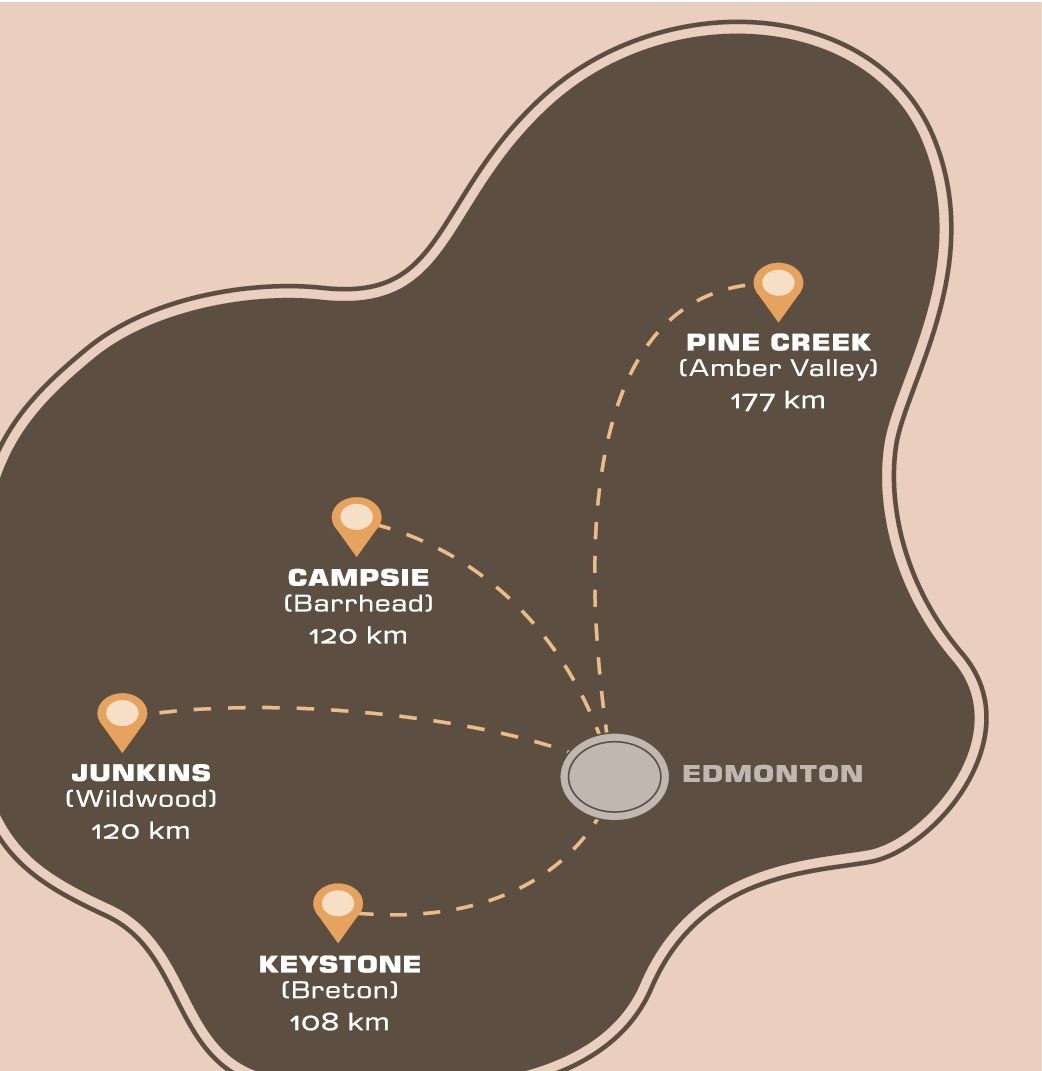

Education was valued within cities and the four rural Black pioneer communities formed in the early 1900s in Alberta: Junkins, Pine Creek/Amber Valley, Campsie and Keystone. After churches, schools were next in line for creating a sense of community for the new Albertans. In Amber Valley, the largest of the communities, a Black teacher named George Cromwell was assisted at times by his wife Alice. Teaching from 1919 to the early 1950s, they were the longest serving teachers at Toles School District and were a significant educational force within the area. Ontario educated, they also farmed and were able to thus supplement their income when payment from the school board was delayed.

In the 1930s and 40s, other Black teachers associated with pioneer communities joined Mr. Cromwell at Toles School for short periods before moving on to teach in other communities. With predominantly Black teachers and students, Toles School provided a welcome opportunity for young Black teachers to work without encountering racism from colleagues, students or parents (although there were other tensions) and some were able to share knowledge of Black experiences with their students.

“I am picking out all the great of the race to show to the colored people here and wherever I have taught. Of course,… I doubt that I would bring this out in an all-white school, unless they asked me to,” said Alice Cromwell in an interview with researcher Charles Irby.

Alice Cromwell also remembered teaching in all-white schools near Amber Valley and how, in one instance, a parent removed his child from her class once he realized that she was “coloured.”

“That was nothing but prejudice, absolute,” she said.

GLENBOW ARCHIVES

Ruby Edwards conducting a class at Grassland School, Amber Valley, Alberta, 1959

Attending normal school for teacher education was often expensive and involved working additional jobs. Black teacher Gwen Hooks, whom I interviewed for a project, reported that her teacher education experiences in the early 1940s were generally positive, but she did remember one particular incident of racism when the professor used a racial slur that caused her to walk out of the class. When she had to report to the school principal, she assumed she would be in trouble, but instead he said that the professor shouldn’t have used that expression and that he would apologize to her and she could go back to class.

Later in her career, she experienced discrimination when she applied for a transfer to another school and “some of the trustees on the school board” voted against her employment. (This outcome was the result of an earlier community drama performance including “Black-face” actors and racial slurs that led to heightened racial tensions.)

Teachers from the Caribbean—1960s

With the coming of qualified and practising Caribbean teachers to Alberta in the 1960s, the Black teaching force became more diversified in terms of origins—no longer just descendants of early pioneers. Teachers from the Caribbean and other commonwealth countries were invited to Alberta to fill what was a severe shortage of teachers.

These teachers possessed skills and expertise that were regarded as meritorious and in line with the 1962 Regulations of the Canadian Immigration Act, which marked a significant shift away from an overt racist emphasis on immigrants’ race, colour and national origin, in favour of basing immigrant selection on their education, training and skills.

The following account highlights the experiences of teachers who arrived with certificates and taught in schools, mainly outside the cities.

There are no detailed records of how many teachers came specifically to Alberta in the 1960s, but based on my conversations with teacher Etty Cameron, we estimate that there were up to 70 Caribbean teachers. Many learned about job opportunities through advertisements in local island newspapers, while others had friends already in Alberta who encouraged them to migrate.

Several of the men and women came with their families while others were single. Some teachers were fortunate in having prearranged accommodation in the community or on the school site. For others, trying to rent long-term accommodation in a city was not straightforward. One teacher reported that, to avoid direct discrimination, she informed the landlord ahead of meeting that they were Black.

The teacher shortage that lead to this influx of Caribbean teachers was most pronounced within the newly emerging Northland School Division. In the article, “The School in the Forest,” J. W. Chalmers suggested, the “schools had only recently been elevated from the humble status of mission schools. Half a dozen others had existed for 20 years or so as Métis Colony schools. Some were located in tiny settlements, a few in ancient fur trading centres.”

While some of the newly arrived teachers were familiar with rural communities in the Caribbean, several still experienced culture shock at life in isolated northern Alberta communities.

”In [Town A], the strangest thing was that the children came to school on a horse-drawn carriage (they never had school buses),” one teacher reported.

Often, Black teachers were the first persons of African descent seen in these remote areas. Although many of the interviewees stated that the people they encountered were nice and friendly, for others the nature of racist incidents resulted in a reluctance to discuss the issue.

“I don’t want to elaborate on that. It took a lot out of me and my family too,” one teacher said.

Teachers sometimes used the idea of being professional to rationalize their unwillingness to make a fuss and report racism.

“As you build relationships and learn, you kind of transcend that and say, okay I’m smart, so therefore let’s deal with it from an intelligent person’s point of view, and don’t let it be something to get you down,” said another teacher.

Some Black teachers developed strategies to deal with such negativity.

“I refused to accept any abuse on the phone from anybody,” said one teacher.

Within the school system, Black teachers sometimes experienced racism through white parents initially regarding them as not competent in terms of subject knowledge or requesting that their child be removed from class. Cameron said that other parents saw it as an advantage to have their child in the class of a Caribbean teacher, as they were they were well trained in classroom management, maintained discipline and used their spare time to devise creative ways to motivate student learning.

“Caribbean teachers were highly sought after,” Cameron said. “At the end of the school year, requests poured in from parents to have their children placed in a Caribbean teacher’s class.”

Some teachers also noted lack of support from administrators when handling complaints from parents and an underlying belief that Black teachers couldn’t be regarded as Canadians. One Edmonton administrator reportedly asked, while laughing, “Why should I hire you when I have all my Canadian boys here to hire?”

As today, evaluation of credentials and certificates was a significant factor for these teachers, as many were evaluated at lower levels and lower pay with less weighting given to teacher education in the Caribbean. The low evaluation of their credentials meant that some Caribbean teachers had to upgrade high school subjects before they could enrol in university summer courses to gain degrees, increase their salaries and become redesignated as professionals. Teachers who had university degrees in addition to their Caribbean certification were treated more favorably in the evaluation.

Isolation in remote areas was an issue, so some of the young teachers made visits to larger communities such as Edmonton or Leduc to keep in touch with fellow Caribbean folks. In Edmonton, the University of Alberta provided a place where Caribbean students and community members socialized. Other teachers adopted community-based extracurricular activities such as skating and curling. A few Caribbean teachers reached out to Black teachers from the early pioneer community who were teaching nearby in the Amber Valley or Breton area. This meeting of the two historically different communities marked the tentative beginnings of the formation of a broader Black community within the province.

By the early 1970s, opportunities changed and certified teachers from the Caribbean could no longer teach on arrival; they needed additional education before they could enter classrooms. The door was closing.

Concluding, although small in numbers, and despite racialized incidents at work, Black teachers have contributed significantly to educating young Albertans, becoming role models and inspiration for students, being active in ATA locals and setting up community organizations. Present-day Black students do not see many Black teachers in the workforce, and Black internationally educated teachers still face the problem of getting their credentials and expertise recognized in Alberta.

Early Black communities

In addition to those living in the cities of Edmonton and Calgary, Black pioneers in the early 1900s organized themselves into four main rural communities: Junkins (now Wildwood), Pine Creek (now Amber Valley), Keystone (now Breton) and Campsie (now Barrhead).

Junkins was the oldest community, with pioneers arriving there in 1908. Amber Valley became the longest lasting community, with its own church, post office and school (est. 1913). Black families arrived in Keystone starting in about 1911.

For further reference:

Carter, V., and Carter L S. 1990. The Window of Our Memories, Volume II. St. Albert, Alta.: Black Cultural Research Society of Alberta, 567–9.

Hooks, G. 1997. The Keystone Legacy: Reflections of a Black Pioneer. Edmonton: Brightest Pebble Publishing Co.

Kelly, J. 1998. Under the Gaze Learning to be Black in White Society. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing.

Shaw-Cameron, E. 2009. Roll Call: Caribbean Teachers in Alberta Schools. Edmonton, Alta.: Self-published.